With the nationwide Parliamentary elections in Norway occurring in just over a week, The Data Times has put together an in-depth forecast predicting everything from the nationwide vote share of the two-party blocs to the seats won by each party in all 19 electoral districts. In this article, I’ll outline the methodology behind it and provide regular updates ahead of the election.

Vote Projections

The nationwide vote share of each party is relatively simple to project using a weighted average of all recent polling. While some of our weighted averages, such as the one used for the Donald Trump Approval Tracker, have several variables (including pollster accuracy and reliability), our Norwegian Tracker only accounts for recency, time of surveying, and sample size. This is because Norway doesn’t have the wide range of polling institutions that the U.S. has. Additionally, they’re all relatively well-regarded, making it redundant to attempt to score their reliability. Our tracker also tries to encourage polling variability to minimize any potential outlier results from one pollster by only allowing two polls from each firm in the nationwide tracker at a time.

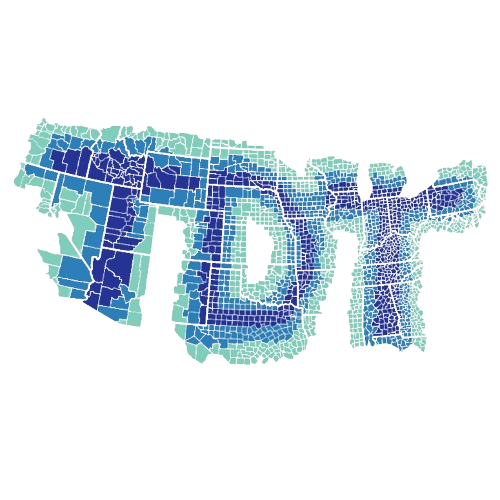

Vote share projections for each electoral constituency are significantly more complicated, but they’re also necessary. Norway uses a modified form of proportional representation for its elections on a district level, apportioning its seats based on a combination of population and geographic size. This is essentially Norway’s implementation of the idea that rural voters should be given more representation, because they’re more dispersed across the country and wouldn’t have enough electoral strength without it. The caveat to this is that regions with fewer seats tend to be less representative of their district’s population.

Additionally, most constituencies don’t have a lot of polling. To account for this, a large part of the constituency forecast is made by applying a proportional swing to each district based on their 2021 results, using the nationwide swing from 2021 to current polling. Districts that have a lot of polls by themselves are less reliant on the nationwide swing, as it’s a dynamic metric. For example, the decently polled district of Hordaland only relies on the nationwide swing for 57% of its projection, whereas the more sparsely polled region of Finnmark uses the nationwide swing for 68% of its projection. The nationwide swing also cannot make a projection exceeding the margin of error for every poll in a district. If this happens, the projection is capped at the bounds of the closest poll to that projection.

Norway uses a modified version of the Sainte-Laguë method to allocate seats for the Storting (Norwegian Parliament) in each district. Essentially, it works by calculating a “quotient” for each party, equaling a party’s votes divided by 0.7, added to the number of seats already allocated. The normal Sainte-Laguë method adds the number of allocated seats to 0.5 rather than 0.7. Norway uses this modified version in order to raise the threshold for smaller parties to start earning seats.

To make up for this, each constituency has one seat reserved as an “adjustment seat,” totaling 19 of the 169 seats in the Storting. To qualify for adjustment seats, a party needs to earn at least 4% of the national vote. As of writing this on August 31st, all nine mainstream parties in Norway are on track to meet this requirement. Adjustment seats are calculated using the same modification of the Sainte-Laguë method, but on a national level rather than a district one. If a party earns seats without meeting the 4% national threshold or earns more seats than entitled to if elections were conducted on a nationwide vote, its seats are taken out of the equation, and the party isn’t eligible to receive adjustment seats. As of writing, the Progress, Center, Conservatives, and Labour parties are projected to earn more constituency seats than they would be entitled to on a national vote, making them ineligible to earn adjustment or “leveling” seats.

The final important thing to note for this forecast is that Norwegian political parties are mostly divided between the two major blocs of the country. The “Red Bloc” consists of the Red, Socialist Left, Green, Labour, and Center parties and is regarded as the country’s left wing. The “Blue Bloc” consists of the Liberal, Christian Democrat, Conservative, and Progress parties and is regarded as the country’s right wing. While these blocs are electoral alliances rather than institutional systems, such as the two-party preferred vote in Australia, they’re far more binding than standard coalitions in most countries. When looking at the seat and vote share projections displayed above, view them with the nuance of these blocs rather than the individuality of the multi-party systems used in most other Western democracies.

Superb analysis!

It does appear that the Centre Party can play the role of kingmaker.

Since Vedum forced this election by withdrawing from the previous coalition,

he may either increase his demands on Store or offer support to the Blue Bloc.

There is a growing ideological difference between Labour and Vedum.

Whether Vedum’s rightward shift reflects the overall Centre position remains to be seen.