There is a growing demand among America’s youth, especially those who identify as Independents, for a new political party in the US. This idea is not new and can even be traced back to polling from 2018, where 57% of Americans stated that a third party was necessary. The desire for political change is evident even in polls that ask the question indirectly. A YouGov poll conducted back in April had favorability for the GOP at just 41%, with the Democratic party at a mere 34%. Despite the best efforts of the American political establishment to limit ideological representation in government, it is clear that the US voting population wants to head towards greener pastures.

Now, there’s nothing physically stopping a third-party candidate from winning an election. In the 2024 U.S. House Elections, 16 candidates ran under the Green Party of the United States. An additional 65 candidates ran for the U.S. Libertarian Party. And most significantly, 90 other candidates ran either as Independents or nominees from minor parties, such as the Working Class Party, which ran candidates in 7 out of Michigan’s 13 congressional districts. Out of the well over 150 third-party candidates who ran in these races, a total of 0 of them actually won.

The Problem

There’s a very simple reason for this. Unlike the vast majority of democratic countries, the U.S.’s lower chamber of Congress is elected using single-member constituencies reliant on a voting system commonly referred to as first-past-the-post. In FPTP, voters are given a list of registered candidates and have the option of electing one candidate on a ballot. The candidate who wins the most of these votes also wins the sole seat in the constituency in which they ran. This idea doesn’t sound too awful at first glance, and it’s used in many other countries besides the US. Canada, the UK, and India also elect their primary congressional chambers using this system. But over the span of centuries, this system has revealed itself to be not only deeply flawed but also severely detrimental to the progression and democratic representation of the societies that utilize it.

When using FPTP, a country’s populace is faced with a choice. Their first option is to attempt to have a variety of political parties representing the entire population. This might automatically sound like the better choice, but it leads to a dangerous phenomenon known as the Spoiler effect. When voters can only voice their opinion on a singular candidate, they have no way of informing the government of their specific preferences on how they want the legislative chamber to be formed if more than two candidates are running. To illustrate where this becomes a problem in a non-political scenario, say your family is trying to decide what to eat for dinner, and they put it to a vote. You have the option of voting for either pepperoni pizza, burgers, or salad. Nearly half of your family consists of vegans, so by default, they all vote for salad (40%). The rest of the family is divided among burgers and pizza (30% for each), so by a 40-30-30 vote, the salad wins by default despite the fact that pizza voters would’ve preferred burgers over salad and vice versa. Even though 60% of the family didn’t want to eat salad and would’ve uniformly preferred one of the other options, salad was elected nonetheless.

I have just described the political system in Canada and the United Kingdom. These nations often boast a “multi-party system,” without having any of the electoral infrastructure to support it. If you take Canada’s most recent general election to the House of Commons as an example, the Liberal party (center-right) won yet another minority government against the Conservatives. In the province of Quebec, a regional separatist party known as the Bloc Québécois (left wing) won 22 seats. Despite this, they lost many of the other races in the province, both to Liberals and Conservatives. In the riding of Montmorency-Charlevoix, a Conservative won even though they only received 35% of the overall vote. BQ voters would’ve most likely preferred the Liberals winning over the Conservatives because the LPC is ideologically closer to the center. This is a prime example of the Spoiler effect, as BQ voters ended up helping elect a party that represented them far less than the LPC would’ve.

The other option for FPTP voters is to resort to only electing two parties. This eliminates the Spoiler effect, but it usually results in a lack of change in a party’s government, as the mainstream political parties are usually not very far away from each other on the political spectrum. In the case of the U.S., both the Democratic and Republican parties are right-leaning. They both support capitalism and the institutions propping it up, and they both have similar war-mongering foreign policy implementations. The media portrays these two parties as widely different, often allowing the false portrayal of Democrats as a “left-wing” party, even though they lack traditional left-wing viewpoints. A figure like Bernie Sanders is viewed as “far-left,” even though he would be considered a centrist in a country with a better electoral system.

Enough complaining, what is the solution?

The concept of varying electoral systems brings us to our next topic, change. Countries like Canada and the UK only have multiple parties because those parties have deeply rooted foundations within their countries’ political history. Parties like the NDP in Canada have been able to maintain a continued existence largely because of how long they’ve been around. The mainstream Conservative Party of Canada has only been around since 2003, as it was an evolution of the old Progressive Conservative Party. In the US, there are many potential solutions to the FPTP problem; the most obvious one is simply using a party-list system that utilizes proportional representation. This system is used by the vast majority of Democratic countries, though it only represents roughly half of the population that FPTP does.

Despite being objectively terrible, FPTP represents roughly half of the population of countries that score at least a 5.00 on the Economist’s Democracy Index. Party-list proportional representation is far behind in second place, though it is used by many more countries and has a global presence. From Norway to Indonesia to Ecuador, proportional voting has been widely successful. Combining the three most used of these proportional voting systems paints a clearer picture, as roughly 45% of democratic populations live under these systems of governance.

To put it simply, proportional voting systems exist in many forms and are used for the primary goal of forming a more representative legislative body. Usually, they take the form of multi-member constituencies (think of a U.S. House district, but larger and with multiple seats). In a party-list system, voters are given a ballot with the names of political parties rather than candidates. Then, seats are assigned to the assembly/congress/parliament proportionally based on the vote share of each party. If a party wins 40% of the vote, they earn roughly 40% of the seats. In many countries, this ends up forcing parties to form coalitions with others, as no single party ever earns enough seats to have a functional majority.

This system has a lot of major benefits. The most direct being that the spoiler effect is heavily reduced, and can even be eliminated in voting systems like single transferable voting, which is a combination of RCV (ranked choice voting) and proportional allocation. This effectively allows third-party candidates to not only win a few seats but also achieve significant representation in government. A side bonus of making it easier for minor parties to have influence is that the major existing political parties can be placed more accurately onto the political spectrum from a local cultural viewpoint. Bernie Sanders wouldn’t have been viewed as a radical leftist if there were suddenly a successful American Communist Party that managed to get even 5% of the House.

Across the vast channels of social media, I’ve seen countless attempts made by people and small groups to create more political parties in the US. Whether it be the Progressive Party, the Forward Party, the Labor Party, or just the current Green and Libertarian parties, there are way too many people who seem to think that the U.S. two-party system only exists as a result of people not making more parties. We have no shortage of political parties or fun Canva graphics and website URLs to make them. The sheer audacity of these groups to consistently antagonize the current political establishment while simultaneously suggesting absolutely nothing to change it is astounding. The Green Party is the most outrageous example of this, parading Jill Stein around every four years while doing nothing to bring about change in the meantime. If figures like Stein were truly anti-establishment, they would be members of groups like the Equal Vote Coalition rather than the “let’s see how we can leech more Democratic voters this time around” association.

The Success of Proportional Voting

In the graph displayed above, voting systems that utilize complete proportional allocation are displayed as stars. With just a quick analysis, it becomes evident that this system is far better than FPTP. The country with the highest rating on the Democracy Index, Norway, uses proportional allocation. The country with the highest share of seats that belong to third parties, Belgium, uses proportional allocation. The country with the lowest rating on the Democracy Index that still sits above a 5 uses FPTP, and a plurality of the countries that lack any third-party representation use FPTP. If Americans truly want more political parties, they need a proportional allocation system.

The implementation of proportional selection is not the only thing that the U.S. needs to change if it wants a more representative and politically diverse Congress. In 1929, the U.S. House was arbitrarily capped at 435 representatives. This number might’ve been fine at the time, but its nonsensical restriction has resulted in the exponential deterioration of the quality of the House’s representation over nearly one hundred years. This has made the U.S. the second least representative democracy in the world, only beating India in terms of the average number of people per representative. The House is now nearly three and a half times less representative than it was in 1929. If it were never limited, we’d likely have somewhere around 1,485 representatives today. Indonesia, a country with 100 million fewer people than the U.S., has a House of Representatives with more than 100 additional members than the U.S. House. It’s also important to note that Indonesia has a party-list proportional voting system.

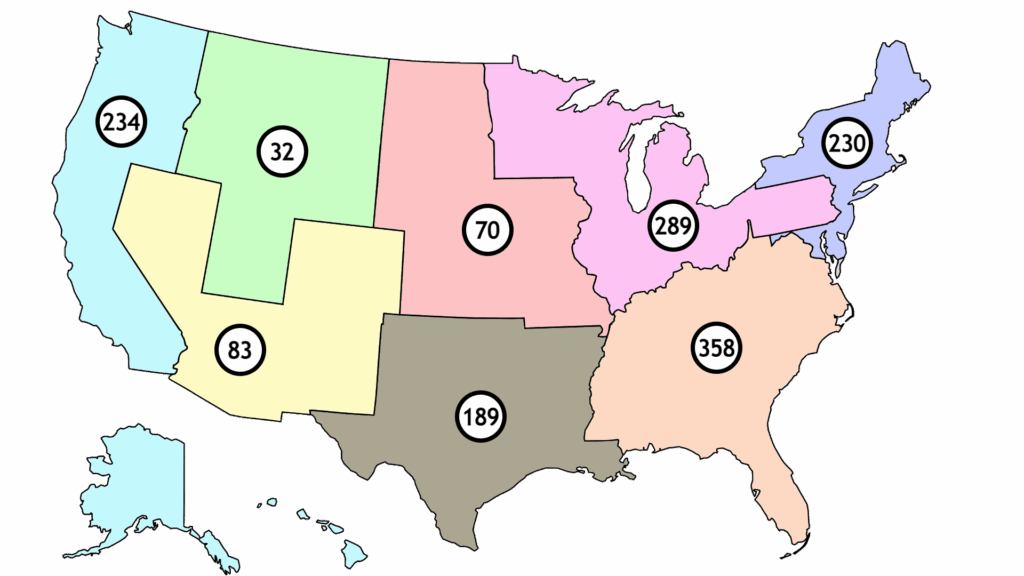

The movement to uncap America’s lower chamber of Congress has gained a lot of momentum, but it wouldn’t be truly successful by itself without proportional representation. Additionally, multi-member constituencies could be drawn long-term or could even be made permanent, making the districting process much easier and nonpartisan. Gerrymandering is already a significant issue in the U.S., so creating more districts to draw will only provide more opportunities for lines to be made unfairly.

The map displayed above is an outline for a potential multi-member constituency system in the U.S., with the seats for each region being displayed in the center. This is by no means a finalized recommendation, but I consider it to paint a generally pretty good picture in terms of separating some of the larger political and cultural blocks of the country.

Complete proportional representation isn’t the only form of proportional allocation, either. Some countries, like Germany and Mexico, use a system known as mixed-member proportional representation. This system combines single-member constituencies with a party-list vote. In Mexico, this takes the form of 5 multi-member constituencies (much like the 8 displayed above). In Germany, the party-list vote is statewide, but parties can only qualify for it if they receive at least 5% of the nationwide list vote. A nationwide party-list is typically more representative, but its implementation could alienate some of the more traditional voters in the U.S. who would prefer to still have some form of local representation. Mixed-member majoritarian representation, a similar system, ensures the allocation of some seats to proportional representation while still leaving the majority to FPTP. While I’m not particularly a fan of any system that uses single-member FPTP districts on a federal level, Mixed-member majoritarian representation has still proven to be effective when it comes to third-party representation.

The chart displayed above reveals many of the strengths and weaknesses of different electoral systems. Party-list proportional representation is the only system where the average person lives under a government controlled by a majority third-party rule. Considering how many countries use it, it’s also relatively consistent. A general average across all countries still brings the 3rd-party control figure near 40%, whereas FPTP is completely at the bottom of the list, with third-party control mostly in the single digits. Clearly, this is a problem that needs desperate and immediate attention. Allowing powerful governments to be controlled by two ideologically similar parties is dangerous not only for said country’s local growth, but the progression of global society as a whole. The fact that the population-based average of third-party representation under FPTP is below 5% is simply a smoking gun of the system’s dysfunction. Countries like the U.S. and India are the two greatest culprits of this figure, as the two alliances in India function relatively similarly to the two parties in the U.S.

Back on to the topic of actually functioning electoral systems, the most consistent one on the list is mixed-member majoritarian representation. Both the country-based average and population-weighted average have third-party control just above 30%. From my perspective, the 30-45% range is ideal for combined third-party control. While third parties need to have significant representation when combined, there will always be great value in the stability of having two mainstream parties. Democratic governments, like all other systems of ruling, are very fragile. Having two primary opposing forces that consistently have at least some control in government can be a very good thing. This fact is the biggest redeeming quality of mixed-member majoritarian representation. Despite maintaining much of the status quo, it still encourages progression and more adequate representation.

There are a few other electoral systems on the list that I haven’t yet discussed in detail. Runoff voting and plurality block voting are both examples of systems that, by default, are better than FPTP. Unfortunately, that isn’t saying much, and all of these systems combined only account for 3% of the population living in democratic countries. Most of that 3% is runoff voting, which is essentially just a version of first-past-the-post where a nation’s populace is forced to choose the two-party option. By requiring a 50% majority to win an election and eliminating candidates that don’t achieve the highest levels of support, the spoiler effect is significantly reduced. However, the true desire for change and third-party representation remains unfulfilled. This remains true even in ranked choice voting, as RCV is essentially just multiple rounds of FPTP voting.

Plurality block voting is another non-proportional system of electing representatives, but, just like proportional voting, it has multi-member constituencies. PBV is a form of approval voting, meaning voters can choose both who they’re voting for and how many people they’re voting for. The winners of this election are simply determined by which candidates earn enough votes to be in the top positions. If a district has 3 seats, the top three-placing candidates will each earn a seat regardless of their specific vote share. In a starkly divided political climate such as the one currently in the U.S., this would work relatively well to adequately represent a somewhat even split between parties. However, if voters truly want change and if parties ever wanted to run multiple candidates in one district, this concept could very easily fall apart.

Let’s say we have a plurality block voting election in a 3-seat district. John and Josh belong to party A, and both decide to run in the election with hopes of earning two of the district’s seats. They share very similar political ideas, but John was able to raise more money for campaigning and has broader name recognition. Support in Party A is very fragmented and is composed of many independents who won’t vote for a candidate based solely on political affiliation. On the other hand, Party B has consolidated its support without significant bipartisan appeal. After the election results are revealed, Party B receives 2 out of the 3 seats in the district despite having less support on average. I pointed out this scenario because it’s a relatively unique criticism of this system. It’s important to note that, alongside this, block voting also encourages strategic voting and leads to the Spoiler effect in races that have third-party candidates running. This is the ultimate problem with plurality block voting, as it’s just another system masquerading as an adequately representative bureaucracy while simultaneously suppressing any real change.

While there are things that can be nit-picked about any and every electoral system, the most important takeaway to get from this analysis is that the vast majority of ideas and reform proposals for new systems of elections in the U.S. are far better than the current FPTP, single-member constituency, plurality voting system. There is not a single country that uses FPTP for its lower or unicameral legislative elections that scores higher than 9 on the Economist’s Democracy Index. Furthermore, there are only two autonomous governments out of the more than two hundred documented in the index that are even characterized as a “Full Democracy.” Third parties in the U.S. will not and cannot ever be both successful and truly representative of their constituents if we continue to use an electoral system that only permits the existence of the same two allegiances that we’ve had for 171 years.